In just a few weeks' time we will pass the anniversary of one of most profound economic policy decisions in Australia's modern history. I refer of course to the decision taken by the Hawke Government in December 1983 to float the Australian dollar and to abolish most restrictions on the international movement of capital.

The decision had been a long time coming. The possibility of a float had been contemplated for years. But the right combination of intellectual climate and circumstances did not arrive until 1983. When it was taken, the decision was a key part of a sequence of very important decisions that opened up the Australian economy and its financial system to international forces, and which changed it profoundly.

Much has been written about that broader reform process. I will speak just about the floating of the dollar itself. I shall pose, and offer answers, to several questions. Why did we float? How has the market developed? How has the exchange rate behaved? What difference did the float make for monetary policy in particular and the economy in general? Has the currency been ‘misaligned’ in ways that have been damaging? And what can be said about intervention?

1. Why did we float?

In a nutshell, I think it is true to say that Australia finally floated the exchange rate because the feasible alternatives had been shown to be ineffective. We had tried just about all the currency arrangements that were known to human kind, with the exception of a currency board: a peg to gold/sterling, a peg to the US dollar, a peg to a basket and a moving peg. All proved ultimately unsatisfactory.

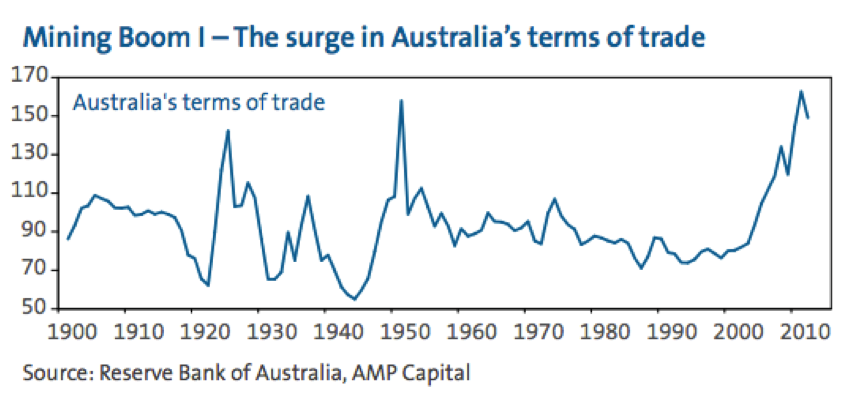

From first principles it could be questioned whether Australia, a country that on occasion experiences quite large shocks in the terms of trade, should have had a fixed exchange rate. The background was the complete breakdown of the international trade and financial system in the 1930s followed by war, which left private capital flows small, central banks and governments dominating capital markets and a distrust of the price mechanism generally. The experience of the early 1950s, however, showed how hard it could be to maintain stability in the face of terms of trade shocks with a fixed exchange rate.[1]

By the early 1980s the intellectual climate had clearly changed. Things had moved on from the post-Depression set of assumptions. More people were conscious of the shortcomings of the regulated era, and were prepared to argue for allowing market mechanisms to set prices and allocate resources.

So there was a case for exchange rate flexibility on ‘real’ or resource allocation grounds. There was also one based on monetary grounds. On the one hand, a fixed exchange rate with a suitable major currency can serve as a ‘nominal anchor’ if we are prepared to accept the monetary policy of the other country through all phases of the cycle. The countries to whose currencies we had pegged, however, had their own circumstances and policy imperatives that evolved differently from our own. Private capital flows had become much larger and our commitment to make a price in the foreign exchange market meant we could not control liquidity in the domestic money market. Inflows of funds in anticipation of a revaluation led conditions to become too easy, and outflows in anticipation of a devaluation tightened up the system. By the early 1980s, with inflation quite high, the lack of monetary control was a serious problem. This was the situation in the lead-up to the decision to float.[2]

2. How has the market developed?

Thirty years ago, the Australian foreign exchange market was relatively small and underdeveloped. At the time of the float, the participants in the market were primarily the domestic commercial banks, though this quickly changed after a number of foreign banks were given licences, increasing competition significantly. After the float, the market matured and grew. Today the Australian dollar is one of the most actively traded currencies. Global daily turnover runs at about $460 billion.[3] The AUD/USD is the fourth most traded currency pair, accounting for just under 7 per cent of global foreign exchange turnover. Compared with the US dollar, the euro or yen, these are small numbers but compared with currencies of several other countries whose economies are noticeably larger than Australia's, the size of the AUD market is remarkably large. It offers the full range of foreign exchange products.

These days more of the trading activity in our currency occurs outside our jurisdiction than inside it, a pattern that is common to most currencies. This reflects the role of international financial centres such as London, which retains a dominant role as a financial hub. Other centres such as Singapore and Hong Kong have made it part of their national ‘business model’ to provide an environment conducive to major financial firms setting up to offer a full menu of financial services to the global investor community. Most countries that are not themselves international financial hubs find that an increasing proportion of trading in their currency takes place ‘offshore’.[4]

3. How has the exchange rate behaved?

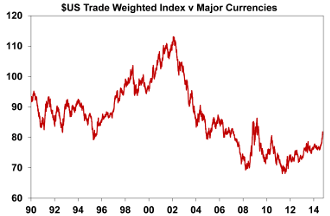

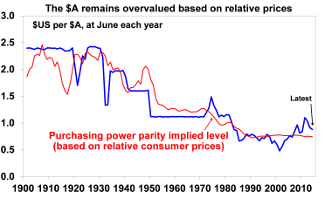

At the time of the float, the Australian dollar against the US dollar was actually not very different from its current value (Graph 1). It was worth about 90 US cents in December 1983. That was down from its highest point in the 1970s under the fixed exchange rate system, of US$1.4875. The trade-weighted index was 81 (today about 72), down from a high of around 120. People forget how high the exchange rate was for much of our history.

Graph 1

Click to view larger

Initially after the float, the exchange rate rose for some months before settling back. There was a further very distinct leg down beginning in early 1985. There was quite a lot of drama at the time – this was the era of credit rating downgrades and ‘banana republics’. I think there was a genuine fear at various times that the currency might simply collapse to some ludicrously low value.

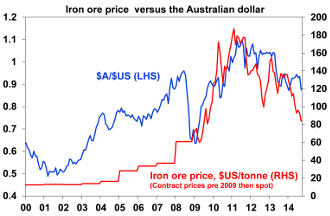

With the benefit of that most powerful of tools, hindsight, one can observe that the currency had by the mid 1980s adjusted to a lower mean value, around which it fluctuated for nearly 20 years. One can further note that those trends had some association with developments in Australia's terms of trade (Graph 2). From this vantage point, the market might be argued, on the whole, to have moved the exchange rate to about the right place. And despite the occasional worries about large downward movements, there was probably less high drama associated with them than would have accompanied decisions to devalue a fixed exchange rate.

Graph 2

Click to view larger

Some trends did seem less explicable, such as when the exchange rate fell below 49 US cents in March 2001 and lingered at very low levels for a while. This was in the wake of a slowdown in the Australian economy, but was also the era of excitement over America's so-called ‘new economy’, and the sense that Australia was an ‘old economy'.[5]

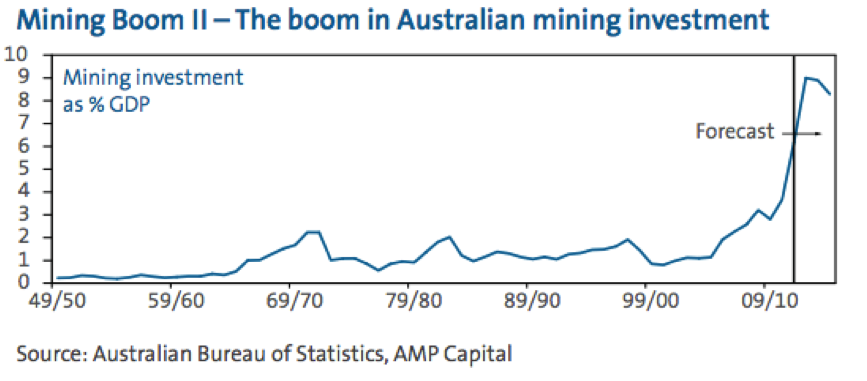

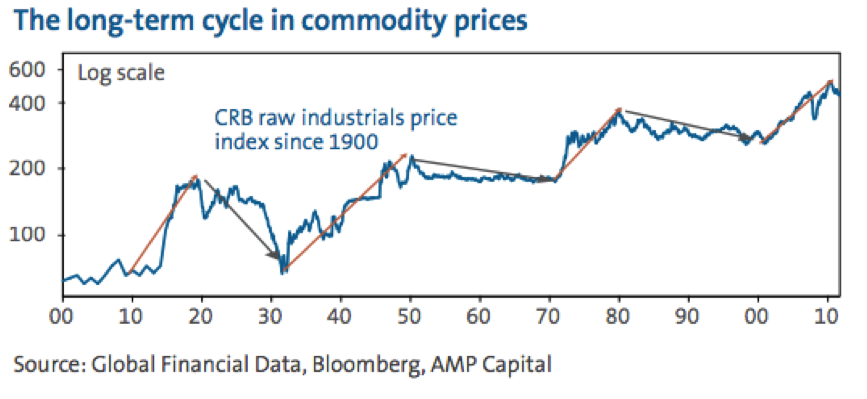

The ‘old economy’ elements like mining would come into their own only a few years later. In 2001, the terms of trade were already rising, and a powerful upswing ensued over the next decade. Even those who were prescient enough to understand the importance of the rise of China have, I suspect, been surprised by the extent of increase in Australia's terms of trade and its longevity. And of course this trend has carried Australia's currency to historically high levels – back, in fact, to about where the floating journey began thirty years ago.

Has the mean value around which the currency fluctuated from the mid 1980s to the mid 2000s now given way to something higher, or will it reassert itself? That is a fascinating question.

4. What difference did the float make?

For the Reserve Bank in its monetary policy responsibilities, the float made all the difference in the world. We no longer had an obligation to stand in the foreign exchange market at a particular price. An earlier decision of the Fraser government to issue government debt at tender meant that the Reserve Bank did not have to stand in the government debt market either. As a result of these two decisions – and they were both important – for the first time the Bank had the ability to control the amount of cash in the money market and hence to set the short-term price of money, based on domestic considerations. This is the hallmark of a modern monetary policy. The extent of short-term variability in interest rates declined while, naturally, that of the exchange rate rose somewhat (Graph 3).

Graph 3

Click to view larger

A flexible exchange rate is also a critical component of inflation targeting, which is Australia's monetary policy framework of choice. Admittedly, for some years exchange rate considerations were still sometimes seen as something of a constraint in the conduct of monetary policy. This has been progressively less the case, though, as the credibility of the inflation target has increased.

Even if all the flexible exchange rate did was to allow monetary policy to operate effectively, that was a major benefit. But the float did more than just that. Real exchange rates move in response to various forces affecting an open economy, even if the nominal exchange rate is fixed. Given the slow-moving nature of the bulk of prices, allowing the nominal exchange rate to change makes the process more efficient unless there is excessive short-run variability in the nominal rate. As hedging markets develop the cost of short-run noise is usually lessened. In my view the flexible exchange rate has helped adjustment in the real economy in its own right.

The combination of allowing monetary policy to operate effectively and fostering real economic adjustment is very important. One very telling comparison is between the macroeconomic performance in the most recent commodity price upswing and that in the episodes in the early 1950s and mid 1970s (Graph 4). It is obvious that there has been a first-order reduction in macroeconomic variability on this occasion. The flexibility of the exchange rate has been a major contributor to that outcome.

Graph 4

Click to view larger

5. Has the exchange rate been ‘misaligned’?

The currency has certainly moved through a very wide range over the thirty years since the float. If our metric were some constant target level of ‘competitiveness’ measured, say, by relative unit costs, then we would be drawn to the conclusion that it has been ‘misaligned’ much of the time.

But such a simple calculation alone isn't the right metric. For a start, over the course of a business cycle the exchange rate should move in ways that help to maintain overall balance between demand and supply. In a period of strong demand it will rise, spilling demand abroad by lowering prices for traded goods and services. This lessens ‘competitiveness’ in the short term, but helps preserve it in the longer term by maintaining discipline over domestic costs.

Moreover, the level of relative unit costs in, say, manufacturing, that is ‘needed’ is a function of several factors, including the terms of trade. A country with an endowment of natural resources will find that when those resources command high prices, it will have a high exchange rate and low manufacturing ‘competitiveness’, compared with the situation when the terms of trade are low. The high resources prices draw factors of production towards the resources sector, pushing up labour costs for other sectors and drawing capital from abroad, so pushing up the exchange rate. The terms of trade rise is an income gain, and may well prompt an expansion in investment in the resources sector. Hence aggregate demand is likely to increase, which among other things will also require a higher exchange rate than otherwise to maintain overall balance. These forces diminish ‘competitiveness’ for other traded sectors. At a later stage, when those adjustments to the capital stock have occurred, the exchange rate may be lower than at its peak, though still higher than what would have been observed had the terms of trade not risen.

So it is not surprising that the exchange rate responds to changes in the terms of trade. It is nonetheless striking how close the empirical relationship has turned out to be. Of course it is not to be assumed that the parameters of that particular empirical relationship are necessarily optimal. But nor is the contrary to be assumed. Over the thirty-year period since the float, that relationship seems not to have led to long periods of the economy either having excess demand or supply. Australia has had one serious recession in that time, in 1990–91, and the principal cause of the depth of that downturn was asset price and credit dynamics, not the exchange rate. Overall, variability of the real economy has been lower in the post-float period. While there are several factors at work in producing that result, the flexible exchange rate is clearly one.

My conclusion, then, would be that evidence of large and persistent exchange rate misalignments is actually rather scant over the floating era as a whole. Arguably some of the bigger misalignments occurred under previous exchange rate regimes.

But what of recent levels of the exchange rate? They have been blamed for many disappointing corporate results and triggered numerous restructurings, instances of ‘offshorings’ and job shedding. The only other factor so frequently offered to explain disappointment is ‘consumer caution’. One can imagine that many people would see this as prima facie evidence of the exchange rate being significantly misaligned.

There are a few difficulties in evaluating that claim. First, very high terms of trade can be expected to lead to some loss of ‘competitiveness’, as noted above. Just how much of this would be expected depends, among other things, on how permanent the terms of trade rise is, but this episode has been very persistent so far. The euphemism ‘structural adjustment’ hardly conveys the difficulties faced by firms and their workforces affected by these forces. But a big and persistent shift in relative prices, which is what the terms of trade shift amounts to, was always going to produce some such effects.

A further difficulty in assessing the exchange rate's level lies in that very persistence. The relationship between the exchange rate and the terms of trade has, broadly speaking, continued to hold (Graph 5). Nothing looks very unusual right at the moment. But this relationship is estimated over a period in which the changes were generally cyclical. It is at least conceivable that a large and persistent rise in the exchange rate may have effects on the economy beyond those discernible from the experience of the past thirty years, if previous rises in the exchange rate were not long-lived enough to cause significant structural change. This is a possibility the Reserve Bank has noted in the past couple of years.[6]

Graph 5[7]

Click to view larger

There is at least one more complication in assessing the exchange rate's recent behaviour and that is the extraordinary monetary policy measures that are being undertaken in the major economies of the United States, Japan and the euro zone. These too are outside any historical experience. Such measures are in place because they are required by the circumstances of those economies, but there is no doubt that they have fostered the so called ‘search for yield’. That, after all, was the whole point.

Added to this is the lessening, even if only at the margin, of perceived creditworthiness of a number of sovereigns, while our own sovereign rating has remained at the highest level. This has contributed to an increase in ‘official’ holdings of Australian assets as reserve holders sought diversification.

These ‘yield-seeking’ and ‘diversification’ flows have, no doubt, pushed up the Australian dollar. Quantifying that effect is not straightforward. Models suggest that interest differentials have had an effect on the exchange rate, but that effect is dwarfed by the estimated terms of trade effects. But again, the conditions we have seen are unlike anything seen in the period over which the models are estimated.

The flows have surely been important at times, though not necessarily lately. The available data suggest that foreign holdings of Australian government debt stopped rising in the middle of last year. Earlier flows into Australian bank obligations have also generally continued to reverse over that time. As my colleague Guy Debelle has noted, the most obvious capital inflows in the past couple of years have been in the form of direct investment into the mining sector. Those flows were of course responding to expected returns, but not ones that were affected very much by the interest rate policies in the major economies.

In the end it is not possible to come to a definitive assessment on the extent of currency misalignment at the moment, on the basis of standard metrics (and having regard to the statistical imprecision of such metrics). Having said that, my judgement is that the Australian dollar is currently above levels we would expect to see in the medium term.

6. Intervention

In the early period after the float the Reserve Bank undertook market transactions for the purposes of so-called ‘smoothing and testing’. As the market developed and the Bank gained more experience, intervention became less frequent but more forceful. A key motivation for intervention was often trying to avoid the currency moving downwards too quickly. For most of the floating era, until recently at least, a currency that seemed prone to weakness seemed more frequently a problem than the reverse.

As has been well documented, the Bank's intervention strategy has tended to be profitable over the long run.[8] The success of this strategy was helped considerably by the fact that, for much of the floating era, the exchange rate's behaviour could be characterised as fluctuating around a stable mean. If a situation came along that shifted the mean, the strategy might need to be altered.

It might be argued that this is what has happened over the past five years or more. The terms of trade event we have lived through is without precedent in its size and duration, at least in the past century. The exchange rate has responded. Notwithstanding that, in my view, the Australian dollar is probably above its longer-run equilibrium at present, it is far from clear that we can assume that the mean level we saw in the 1980s to the early 2000s will be the relevant one in the future. In evaluating the merits of intervention, the Bank has been cognisant that the current episode is unlike the experience of the first twenty or twenty-five years of the float. Some very powerful forces have been at work.

A further factor relevant to intervention decisions has been cost. Intervening against the Australian dollar would have involved selling Australian assets yielding, say, 3 per cent, and buying foreign assets yielding much less – in fact earning almost nothing over recent years at the areas of the yield curve where the Bank operates. This ‘negative carry’ would be a cost to the Bank's earnings and therefore Commonwealth revenue.

Now it might be argued that a negative carry for the Reserve Bank, and therefore the Commonwealth, and an acceptance of the associated very large valuation risks, would be a price worth paying, if it corrected a seriously misaligned exchange rate. If such a policy were effective, it could turn out to be profitable, if a fall in the exchange rate offset the negative carry. The point is simply that costs have to be considered alongside the likely effectiveness. Often those who argue for intervention don't work through those costs, or they assume it would be entirely costless. That can't be assumed and the idea should be considered in a cost-benefit setting.

Overall, in this episode so far, the Bank has not been convinced that large-scale intervention clearly passed the test of effectiveness versus cost. But that doesn't mean we will always eschew intervention. In fact we remain open-minded on the issue. Our position has long been, and remains, that foreign exchange intervention can, judiciously used in the right circumstances, be effective and useful. It can't make up for weaknesses in other policy areas and to be effective it has to reinforce fundamentals, not work against them. Subject to those conditions, it remains part of the toolkit.

Conclusion

When the foreign exchange market opened on 12 December 1983, without the Reserve Bank making a price for the first time in decades, people would have been uncertain what would happen. Yet policymakers had tried all the alternatives and the float was an idea whose time had come. It was a profound decision – part of a recognition that Australia was part of a wider world, and that we had to reform our own policy and economic frameworks in order to have the sort of prosperity that we wanted as a society.

On 12 December this year we can expect the exchange rate to move a little, one way or the other, and for this to be reported in a very matter-of-fact way on the news broadcasts. We will be able to get updates on our smart phones and to read seemingly limitless quantities of analysis about why it moved the way it did, and predictions about what it might do next, most of which we shall (sensibly) ignore. We would be able, if we wished, to trade foreign currencies from those devices in a way unimagined thirty years ago. (For the record, I am not recommending the practice.) For the dollar to move around in the market as the various players balance supply and demand is now considered normal, and most of the time it is considered no more newsworthy than the price of milk or petrol, and less newsworthy than the price of houses.

Over the past thirty years, the exchange rate has on occasion been the subject of excitement, concern, even shock. It has acted as a shock-absorber, as intended, but it has also served as a disciplining constraint at times. Generally speaking, that was good for us.

At various times we have worried that the market was behaving irrationally, believing that the exchange rate should have been somewhere other than where it was. And sometimes we were right about that. Yet, looking back, on balance the evidence suggests, I think, that the market has mostly moved the exchange rate to about the right place, sooner or later. We sometimes didn't like the pathway. But if I ask the question of whether I would have consistently done a better job setting that price, even had that been feasible (which it wasn't), I don't think I could confidently answer in the affirmative.

No doubt at some Australian Business Economists' occasion on a future anniversary of the float, these matters will be re-examined. We cannot know what the conclusions will be. But for now, and probably for quite some time to come, we remain best served by the floating Australian dollar.

Endnotes

* I thank Alexandra Rush for assistance in preparing these remarks.[BACK TO TEXT]

- In the early 1950s the Korean War induced a wool price boom, increasing Australia's terms of trade dramatically. Under the fixed exchange rate and without the stabilising effect of an appreciation, the associated increases in national income and aggregate demand led CPI inflation to peak at almost 24 per cent.[BACK TO TEXT]

- Remarkably, the decision was taken as the exchange rate was under upward pressure, only a matter of months after a discrete devaluation had been forced on a newly elected government by large capital outflows.[BACK TO TEXT]

- Figures from the BIS Triennial Central Bank Survey of foreign exchange and derivatives market activity in April 2013.[BACK TO TEXT]

- Should this worry us? At one level it might be concerning that people elsewhere in the world take decisions that have a major bearing on the value of ‘our’ currency. But decisions elsewhere in the world have a major bearing on the price of lots of things we care about: traded products of all kinds, the stock market valuations of our companies, the interest rate on government debt and so on. It is part and parcel of participating in the global economy and being open to foreign trade and capital flows that foreigners have a say in pricing the currency. They can and will do so whether the traders sit in Sydney or Singapore or London. That is a separate question from whether we would benefit from our firms offering more value added in financial services to the investors of the world.[BACK TO TEXT]

- We found ourselves ‘out of favour’ despite the fact that it was almost certainly the use of information technology rather than its production that made for the biggest gains to a society and on that score Australia ranked highly. The price put on our currency by the market seemed at odds with other things and that episode saw the first use of results from a model in a speech by a Reserve Bank Governor to demonstrate that point (see Macfarlane 2000).[BACK TO TEXT]

- See Lowe P (2012), ‘The Changing Structure of the Australian Economy and Monetary Policy’, Address to the Australian Industry Group 12th Annual Economic Forum, Sydney, 7 March.[BACK TO TEXT]

- Graph 5 shows the results from a standard model maintained by the Reserve Bank's staff (Beechey et al. 2000; Stone, Wheatley and Wilkinson 2005). The estimated ‘equilibrium’ level is based on the real exchange rate's medium-term relationship with the goods terms of trade and the real interest rate differential with major advanced economies. In this sense, the estimated equilibrium is the value of the exchange rate justified by these medium-term fundamentals, based on historical relationships. In practice, the terms of trade has historically been the most important determinant of this estimated equilibrium. At any point in time, divergences between the actual real exchange rate and the estimated equilibrium will reflect some combination of the model's short-run dynamics, which include a number of variables that account for financial influences on the exchange rate and an unexplained component. The short-run variables include a financial market-based commodity price measure and variables that capture changes in risk sentiment in financial markets.[BACK TO TEXT]

- See Andrew and Broadbent (1994) and Becker and Sinclair (2004).[BACK TO TEXT]

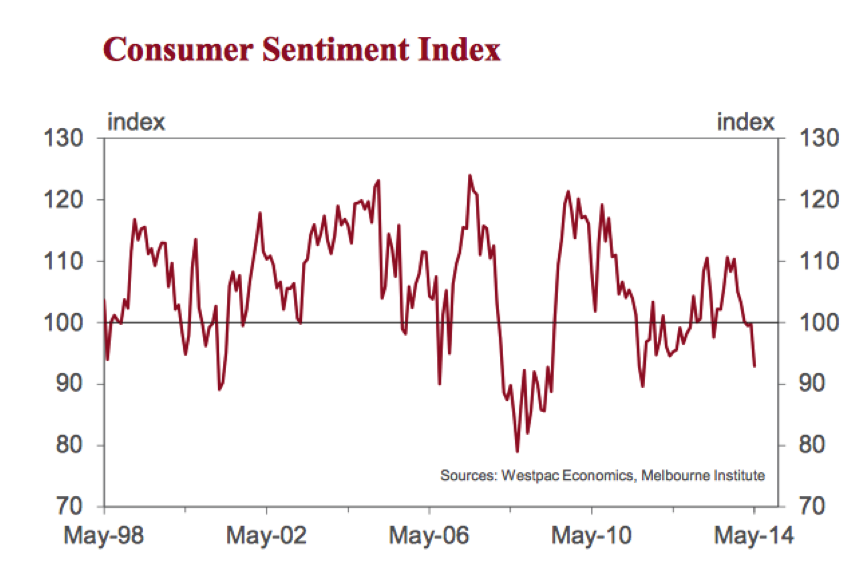

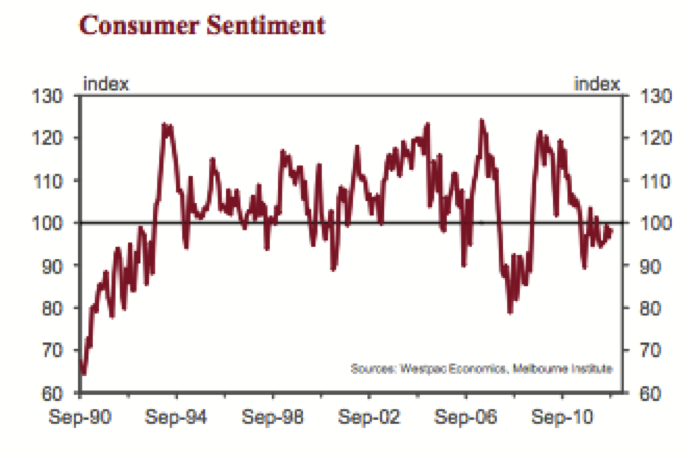

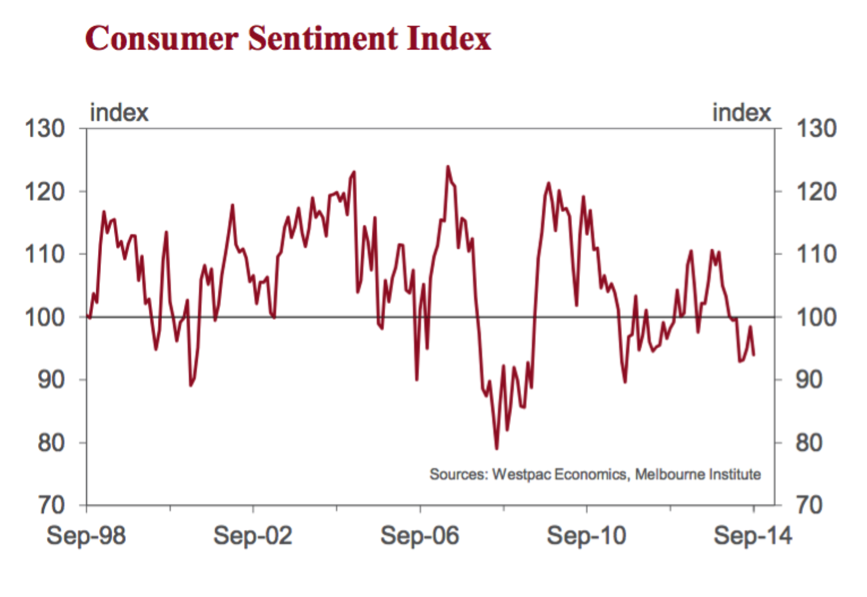

Of most concern here is the five year economic outlook. This component is typically much more stable than the 1 year outlook but the print in September is the lowest for 16 years. It is down 28.6% on its level from a year ago. Concerns around the medium term outlook are likely to make households more cautious. Logically, such concerns indicate that households expect any current economic weakness to be sustained for a considerable period.

Of most concern here is the five year economic outlook. This component is typically much more stable than the 1 year outlook but the print in September is the lowest for 16 years. It is down 28.6% on its level from a year ago. Concerns around the medium term outlook are likely to make households more cautious. Logically, such concerns indicate that households expect any current economic weakness to be sustained for a considerable period.