Key points

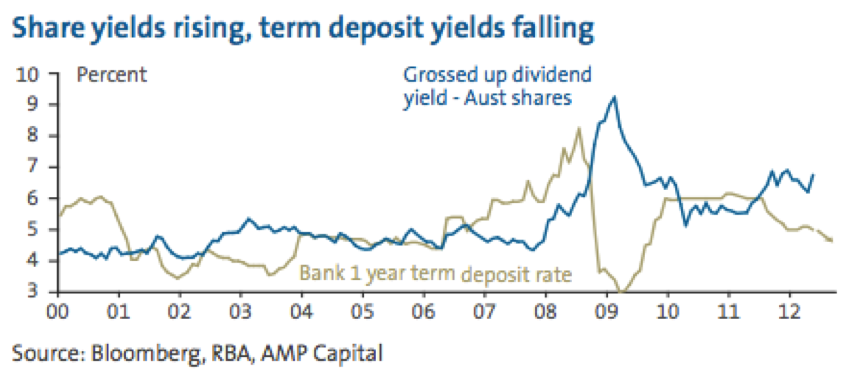

- With yields on shares up and yields on bonds down, shares likely offer a decent return premium for long-term investors notwithstanding ongoing short-term uncertainty.

- However, for those who can’t take a long-term approach, outcome-based approaches or focussing on investment yield are worth considering.

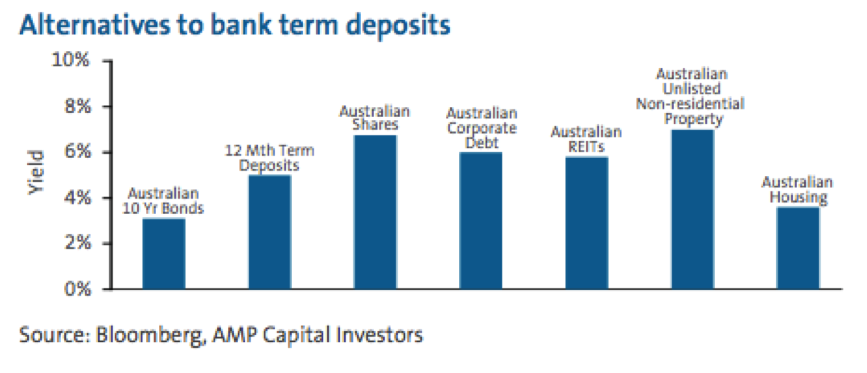

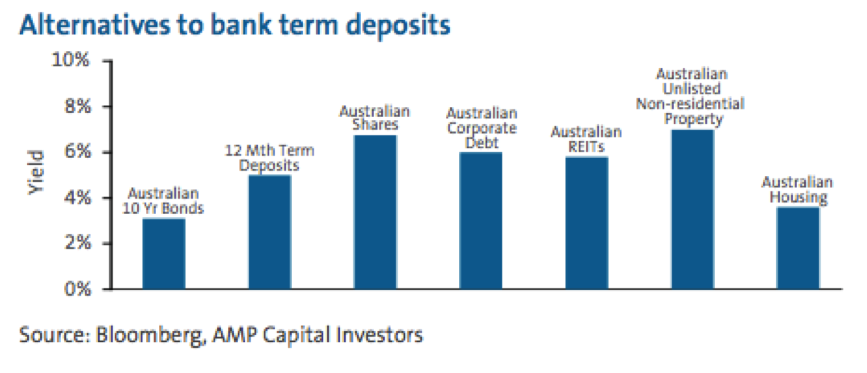

- While term deposit yields are falling, attractive alternative sources of yield can be found in Australian shares, corporate debt, non-residential property and infrastructure.

Introduction

The investment environment remains tough. On a long-term basis, shares and other related growth assets look attractive after several years of poor performance. Against this, Europe and the US are continuing to suffer aftershocks from the global financial crisis, resulting in periodic falls in investment markets as investors run for safety only to be reversed again as government policy-makers swing into action. Meanwhile popular safe havens such as government bonds and bank term deposits are becoming less attractive as yields fall.

So what should investors do? There are essentially three options: sit tight and ride it out; consider outcome-based strategies; or focus on yield-based investments.

Sit tight

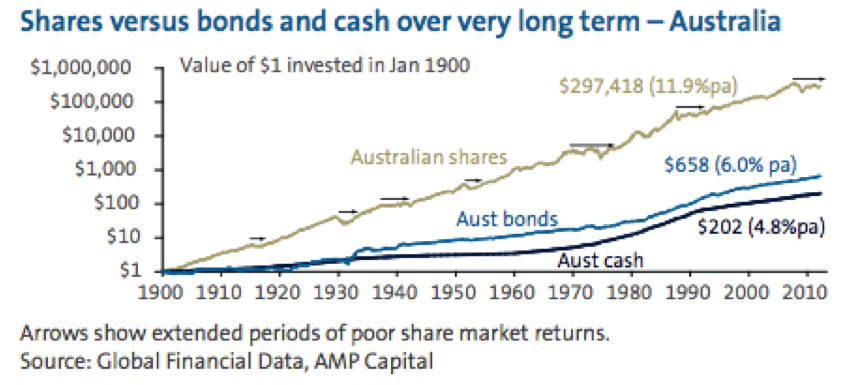

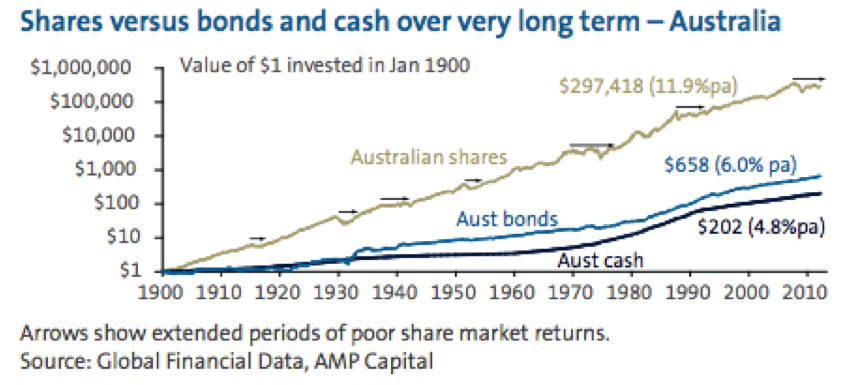

History shows that over long periods of time, shares provide higher returns than cash or bonds. This can be seen in the following chart, which shows that since 1900 Australian shares have returned nearly 12% per annum (pa) compared to 6% for bonds and 4.8% for cash.

In a longer-term context what we are going through right now is not particularly unusual. From late 1969 through much of the 1970s, shares churned roughly sideways (albeit with a 60% slump in share prices along the way). Also, from a high in 1987, accumulated share market returns didn’t reach a new high until 1993. But after each of these episodes, shares resumed generating solid returns.

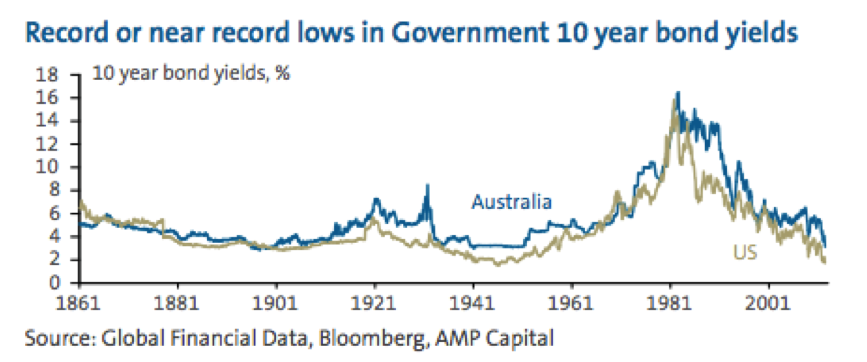

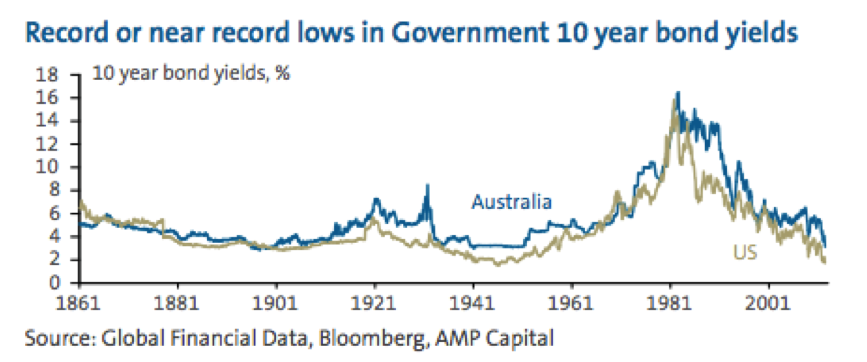

It is also worth noting that over the last thirty years or so government bonds have been in a massive bull market as ten-year bond yields have fallen from around 15% in the early 1980s to record lows in the US now and near record lows in Australia. The Australian ten-year bond yield is now 3.14%, a level which was last seen in May 1941 at the height of World War II. The record low for ten-year bond yields was in September 1897 at 2.9%.

This massive decline in yields from the early 1980s was driven by the adjustment from high inflation to low inflation and more recently by worries about global deflation following the global financial crisis. It has generated huge capital growth and hence returns for bond investors. However, with bond yields so low, the days of high returns from government bonds are behind us. Sure, bond yields could fall below 1% if Japanese-style deflation sets in. But it is hard to see the US Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke or Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Governor Stevens allowing this. In the meantime an investor who buys a ten-year bond today and holds it to maturity will get the spectacular return of 1.74% pa in the case of US bonds or 3.14% pa from Australian bonds.

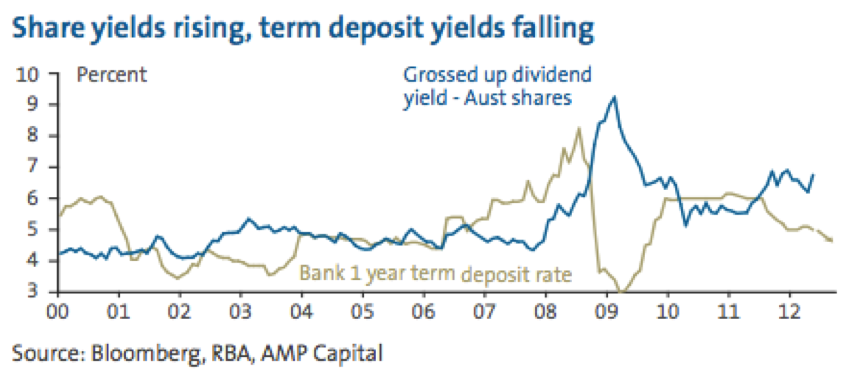

The dividend yield on Australian shares today is around 5% (or 6.5% if franking credits are allowed for). Only modest capital growth of 5% pa will generate a total return of 10%, which is well above the prospective return on bonds.

So while the secular bear market in shares may have further to go, reflecting public and private debt deleveraging in key advanced countries, extreme monetary policy settings and less business friendly governments, at least a lot is already factored in and given current starting point valuations (higher yields on shares and low yields on bonds) shares should provide a decent return premium over bonds. So on this basis it may be best to stay put with previously agreed strategies focussed on the long term.

However, that may be fine for someone who can take a long-term investment horizon, but it may not be so good for those near to retirement or in retirement (like my Mum) and with modest investment balances. Of course it also ignores the opportunities for taking advantage of extreme market moves along the way. So it is worth considering alternatives.

Outcome-based investing

Outcome-based investing involves investing in funds that target a particular outcome in terms of return (say inflation plus 5% pa) or income. The key elements of a multi-asset fund managed along these lines would be a focus on overall risk, highly flexible asset allocation capabilities (often referred to as dynamic asset allocation) and wide sources of market returns. This is in contrast with the traditional approach which involves constructing a benchmark mix based on simplistic growth/defensive categorisations and assuming it will deliver to client risk and return expectations.

Yield-based investing

Another approach, which can be seen as a subset of outcome- based investing, is to focus on assets that provide a decent investment yield. This is attractive because assets with a decent and sustainable yield provide a greater certainty of return in an environment of high market volatility and constrained capital growth. However, many of the traditional options here are becoming less attractive.

The traditional safe asset – government bonds – has seen yields collapse to record or near record lows. Australian ten-year bond yields have fallen to 3.14% and five-year bond yields (indicative of the yield on an Australian government bond portfolio) are just 2.5%. The average yield on global government bonds is around 1.5%, which is all the more amazing given that Japan and the US, which have the highest weight in global sovereign bond indices, have worse public debt levels than Europe.

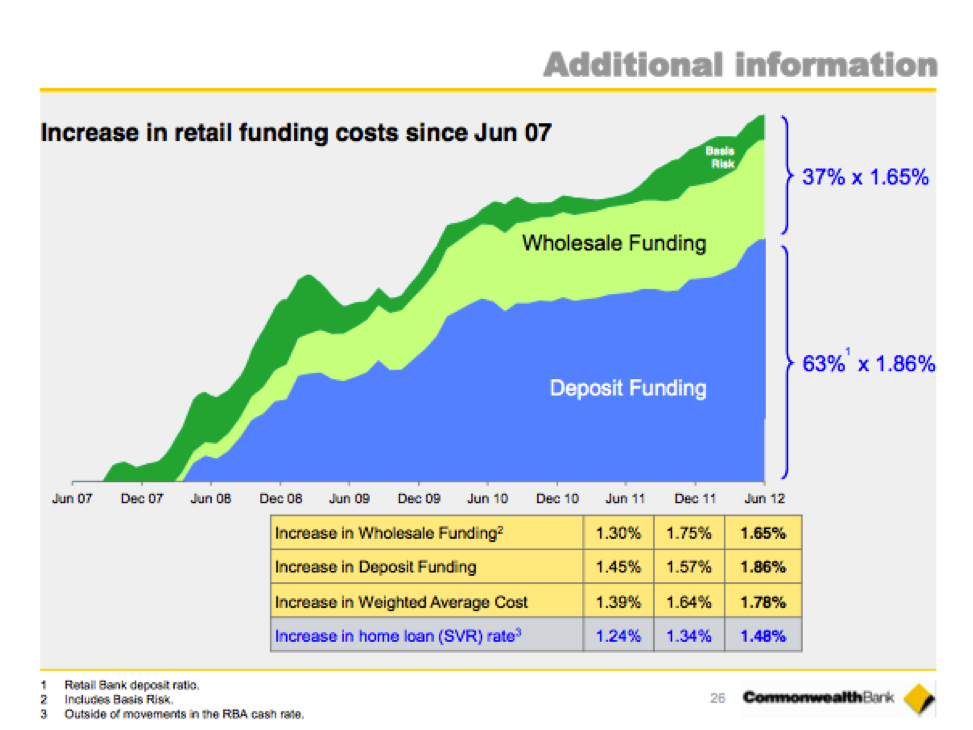

Bank term deposit rates are now falling with the RBA cutting official interest rates. The collapse in bond yields points to further falls ahead, reflecting a combination of increasing global uncertainty, a moderation in growth in China taking the edge off the mining boom, struggling conditions in non-mining sectors and benign inflation. We expect the cash rate to fall to around 3%, which will likely see bank term deposit rates fall to around 4%.

Housing used to be seen as an attractive source of investment yield, but after the house price boom of the past twenty years this is no longer the case, with the rental yield on houses around 3.6% and that on apartments around 4.7%. After costs net yields are around 1% for houses and 2.2% for apartments and after a long bull market, Australian house prices are vulnerable to an extended period of poor capital growth.

However, there are several alternatives to term deposits, government bonds and residential property in terms of assets that provide decent income. See the next chart.

The grossed up dividend yield on Australian shares at around 6.5% is now above term deposit rates meaning that shares are actually providing a higher income flow than bank deposits. Of course, shares come with the risk of capital loss. One way to minimise this is to focus on stocks that provide sustainable above average dividend yields as the higher yield provides greater certainty of return during tough times. Excluding resources, the grossed up dividend yield on Australian shares rises to over 7%, for telecommunication companies and utilities it is around 8% and for bank shares it is above 9%. Furthermore there is evidence that stocks paying high dividends are associated with higher returns over time as retained earnings are often wasted and dividends reflect confidence regarding actual and future earnings. Of course there is no such thing as a free lunch – so the key is to focus on companies that have a track record of delivering reliable earnings and distribution growth over time, where dividends are not reliant on significant leverage and the yield is not high only because there is something wrong with the company.

Corporate debt is a good option for those who want higher yields than government bonds and term deposits but don’t want the volatility that goes with the sharemarket. For Australian corporates, investment grade (i.e. top quality companies) yields are now around 6% and lower quality corporate yields are higher.

Australian real estate investment trusts (A-REITs) used to be a popular alternative to bank deposits but fell out of favour in the global financial crisis as their yields proved unsustainable partly due to excessive debt. However, A-REITs have now refocussed on their core businesses of managing buildings, collecting rents and passing it on to their investors – all with lower gearing. A-REIT yields, at around 6%, are currently the second highest in the world amongst REITs (after France) and the sector seems to be more stable (falling only slightly during the recent correction).

Unlisted commercial property also offers attractive yields, around 7% for a high quality, well diversified mix of buildings, but into the low double digits for smaller lower quality property. Not bad when inflation is around 2%.

Finally, listed and unlisted infrastructure offers yields of around 6%, underpinned by investments such as toll roads and utilities where demand is relatively stable.

Concluding comments

With yields on shares up and yields on bonds down, shares offer a decent return premium for long-term investors despite short-term uncertainty. However, for those who can’t take a long-term approach and/or want to take advantage of short- term opportunities, outcome-based approaches or focussing on income yield beyond bank deposits are worth considering.

This information is of a general nature only and neither represents nor is intended to be personal advice on any particular matter. We strongly suggest that no person should act specifically on the basis of the information contained herein, but should obtain appropriate professional advice based upon their own personal circumstances including personal financial advice from a licensed financial adviser and legal advice. RI Advice Group Pty Limited ABN 23 001 774 125 AFSL 238 429.